While Will is on the road with UIndy baseball, David Barshop finishes out his series on the changes from 2020 with a look at the three batter rule, which continues this season and presumably going forward. Enjoy! - Will

It’s March and Spring Training is officially here! Every little details been set and agreed to by the league and the players, and we’re good to go. Last month, the MLB players union rejected the leagues proposal to include the DH in the National League for the 2021 season. The players realizing that things which worked last year in the pandemic-shortened season were not germane for 2021, also shot down another round of expanded playoffs.

With 2021 bringing a return to normalcy in the game (although 7 inning double-headers and runners starting extra innings on 2nd base will still occur), I wanted to look at one more rule implemented last year that appears to be remaining in place: “the three-batter rule.”

Since Rob Manfred became commissioner in 2015, he has made it his mission to reduce the length of the games. From limiting mound visits, to shortening time in between innings, he has become a champion for speeding up pace of play. Manfred has imposed penalties to batters who step out of the box in between pitches and pitchers who don’t deliver the ball to home plate fast enough during that brief respite. Even intentional walks are now automatically done without a single pitch being thrown.

The reasoning is that baseball has become, or always has been, too slow, and that it’s losing fans who are turned off by the duration of the game.

While these rules don’t affect the integrity of the game (a phrase I’ve found myself using a lot these last couple years, particularly in 2020), and can be ignored by most fans, it is the three batter rule which really changes the way the game is played and managed.

The rule states that any relief pitcher brought into the game must face at least three batters before being pulled. “It is the dumbest rule we’ve ever put in,” said Joe Girardi prior to the kickoff of the 2020 season. He was hardly the only person in the game who felt that way: “Just imagine – and it’s going to happen – somebody loses a World Series game because they were forced to leave a pitcher in the game,” said one anonymous manager, quoted in a Jeff Passan article.

They’re both right. How can baseball minimize part of what is arguably the best and most important part of the (or any) game: the strategy? Managerial strategy is cut in half with this rule. The three-batter rule handicaps them, penalizing the innovation and analytics that comes with creating the optimal, most favorable matchup between pitcher and hitter.

One of my favorite parts of the game was watching two managers methodically drain each others benches and bullpens in the later stages of the game, changing out hitters and pitchers in a chess match that left both of them crossing their fingers, hoping for the best. Sometimes the manager would send up a pinch hitter for the sole purpose of getting the other manager to change pitchers before substituting another pinch hitter. Mostly it was just to get the favorable matchup: lefty against righty and visa-versa.

Forcing managers to leave a pitcher in the game severely affects the outcome. It’s problematic for managers to keep a pitcher on the mound who’s stuck in an unfavorable matchup with the next batter. This might result in more (automatic) intentional walks being given, which also is not optimal. Finding the right matchup to get outs or get runs (depending on which side you’re on) has always been one of the most important part of managing in the late innings.

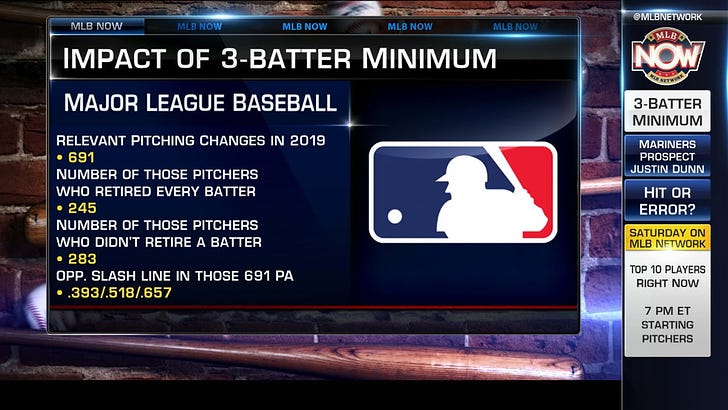

According to the Elias Sports Bureau, in 2019, there were 649 appearances that would not be permitted under the new rules. In 2018 there were 720. This amounts to one in-game pitching change for every 3.74 games. That really is not a lot of pitching changes in the grand scheme of the game.

These pitchers weren’t pulled to waste time, they were swapped out to win ballgames. Hasn’t that always been the point? Besides, what makes baseball special is that there is no clock: the game is finished when it’s finished. It is as if Rob Manfred has added the Commissioner’s Office as a third manager determining strategy in every game.

The rule stands to hurt certain players too: “specialists” like Oliver Perez who’s primary job during the last few years is to come into the game to face the opposing team’s best left-handed hitter(s) and then come out before facing the righties. I’m surprised the players union would let this rule change happen, as it takes money and suitors away from these specialists who come in just to face one, maybe two batters.

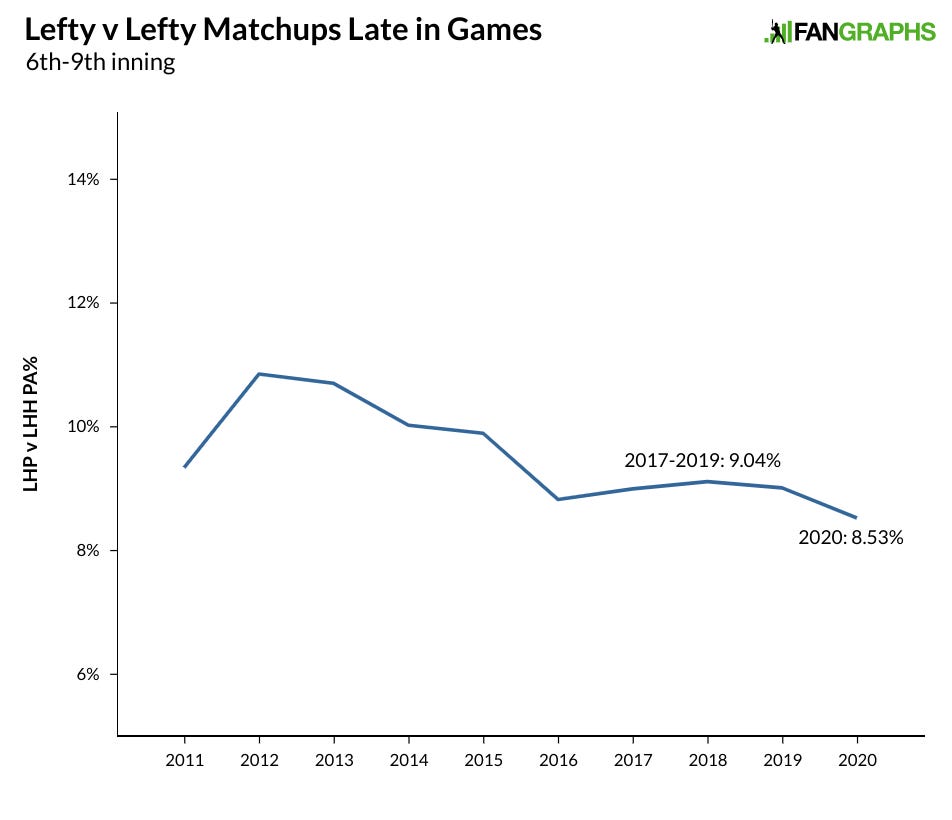

Image courtesy of Fangraphs

Not surprisingly, left-handed pitchers are the ones who are being used less late in games now that the LOOGY (left-handed one out guy) can no longer fulfill his old role.

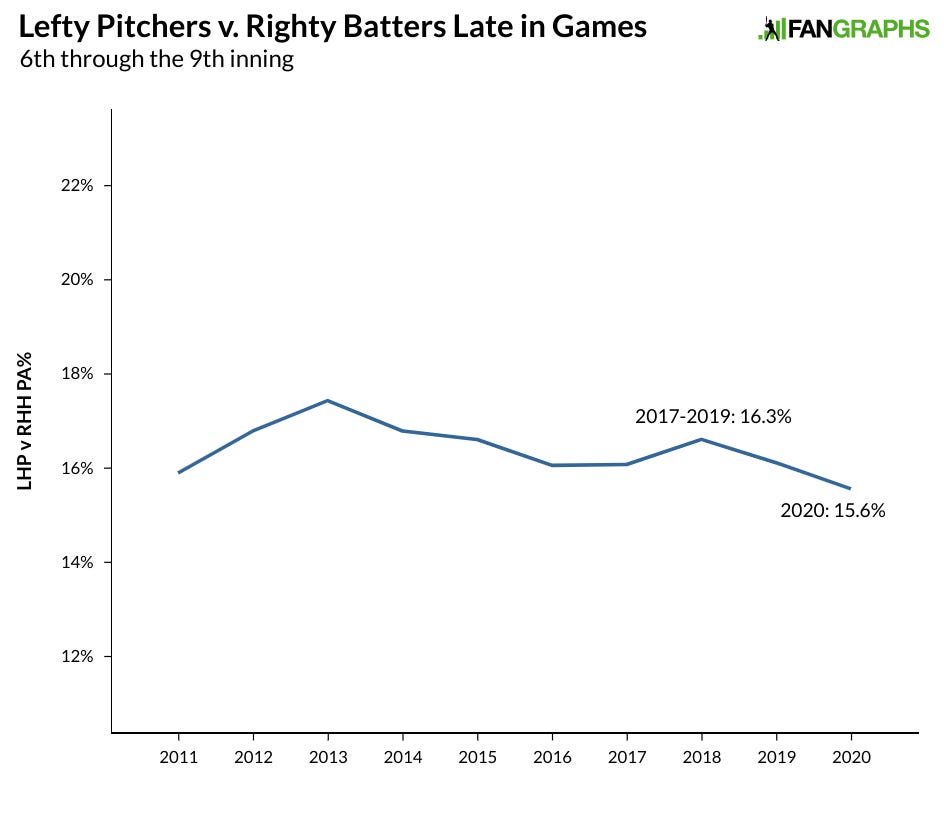

Image courtesy of Fangraphs

This chart also backs that up, as left-handed pitchers are not being used as frequently late in games. How is it fair for one team to be forced to leave in their pitcher, while the other team is free to substitute hitters to get the matchup that they want? It’s not, and it’s leading to changes in the way managers are approaching the game.

Image courtesy of Fangraphs

With righty-righty matchups decreasing during the waning hours of the game, and a decrease in left-handed pitcher usage, it stands to reason that we see in the next graph a large increase in lefty batters facing right-handed pitchers.

Image courtesy of Fangraphs

Well there you have it. That’s what the decline of traditional baseball strategy looks like in numbers and lines. And all of this just to speed the game up a little bit.

But wait, what’s this? The average time for a 9-inning major league game last year, the first with this new rule, did not actually decrease … it went up!!

It took an average of 3 hours and 7 minutes to complete a 9-inning game last year, 2 more minutes than in 2019, and 7 more than 2018. In fact, 2020 averaged the longest 9-inning games in major league history. Figure that one out.

Is it too soon to call the three-batter minimum rule a flop? Well, it depends who you ask. But unlike the other innovative rule changes which dogged the 2020 season, this one has not been a part of the league/union negotiations, meaning that Rob Manfred and the league are willing to give it another try.

At what point do they put this one to bed? There were too many asterisks last year in the game, and this one would add a big one on the 2021 season and beyond if it’s kept around. However, if the games don’t end up getting any shorter, hopefully the backlash from longtime managers and players will put this rule on the chopping block.

There is no place in baseball for rules that handicap the managers and the way they use their rosters. Nothing should be off-limits for them when it comes to winning a ballgame. Now is not the time to sacrifice the beauty of strategy and innovation in exchange for a few extra minutes.

David Barshop lives in Los Angeles and is available for jobs in baseball. He assists with research at Under The Knife.