This tweet got me thinking:

I knew all the numbers, know Marshall’s background with biomechanics, and his … let’s just call them different and difficult ideas about pitching, but I’d never really thought about the shape of that 1974 Cy Young season. While I’ve long advocated for the concept of a Marshall-style reliever, as far back as Tim Lincecum and closest with Andrew Miller in Cleveland, I’d always applied modern concepts to get a pitcher to those numbers rather than looking at what actually happened.

So let’s start with Marshall himself. Ignore all the things that have come after. While Marshall certainly had some of his ideas or at least the base of them in 1974 — especially given his work with Tommy John during his rehab from elbow reconstruction — he didn’t actually use any of them. Marshall’s delivery was very standard for the time and as far as I can tell, Marshall had developed none of the exercises he advocates today.

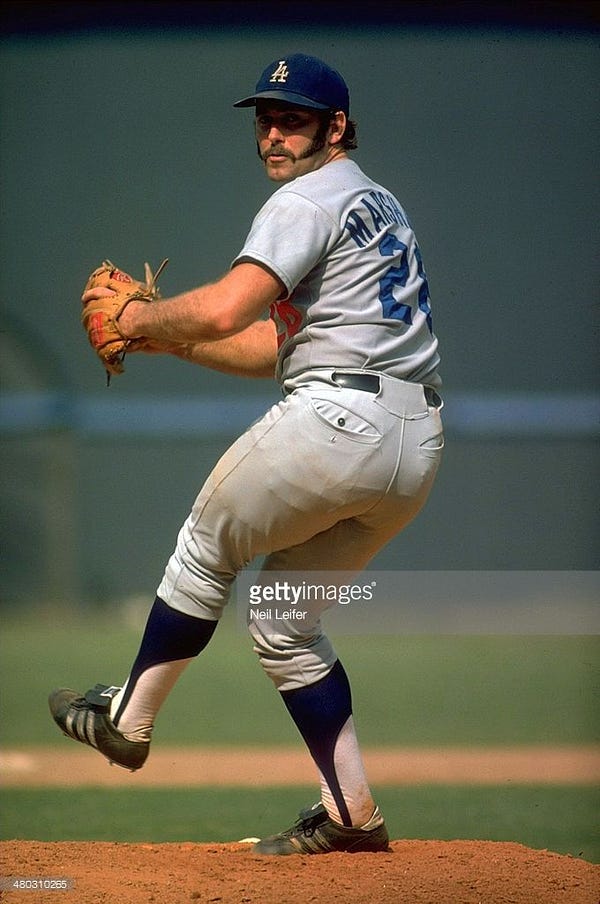

This isn’t the greatest look at Marshall’s mechanics in 1974 and it’s only one pitch, but I don’t see anything that is unusual. He’s listed at 5’10, 180 in that season, which isn’t unusual. Most of the pitchers on that team are 6’1, but Marshall is about the same size as Al Downing. Marshall’s windup, stride, and arm action are about as normal as can be. If anything, he looks loose and low effort, especially given he was pitching to win a World Series.

Again, let’s ignore all that, because it’s not what Marshall did. By his own analysis, he was more of a drop and drive pitcher, which is pretty common for the time. Tom Seaver and Don Sutton, Marshall’s own teammate, were both classic drop-and-drive guys.

Rest days would seem to be a key for someone that pitched over 200 innings in relief, but there’s no discernible pattern. Walter Alston and Red Adams used Marshall most often on no rest, exactly half (53) of his 106 appearances. He got one day of rest 36 times, two days 10 times, three days 4 times, and four days only once. There’s no discernible difference in his effectiveness. Marshall would pitch in seven consecutive games several times during the season, a full week without rest. He once went 13 straight games, which is an MLB record to this day.

There’s also no discernible pattern to how much he pitched in each game, with his per-game innings totals looking like a random number generator created them. He went six innings once and five innings once. The six inning game was one where the Dodgers fell behind early with Doug Rau, Charlie Hough, and Dowling combining for three innings and giving up six runs. Marshall came in and cruised for six, getting the win after holding the Cubs to four hits. All that work - an estimated 79 pitches — and he got a couple days rest after that. With the five inning game, it came in September and he only got a day’s rest after. Marshall took over in the fifth after Geoff Zahn was mediocre against the Reds and closed it out. Marshall wasn’t great, but he kept the Dodgers in the game against the about to be Big Red Machine.

Marshall was incredibly efficient during the entire season, giving up only 56 walks on the year, or about a walk every other time he pitched. His season high was 3 walks and only had multiple walks 12 times. That’s highly efficient, highly effective, and highly unusual, especially given he was striking guys out (143 on the year) and not giving up a lot of hits (191, on 206 innings pitched.) He wasn’t pitching to contact or really pitching ground balls on a consistent basis.

To summarize, Marshall was very good, very efficient, but he wasn’t doing it with any clear pattern. He took the ball, a lot, and went out and threw innings. He’d give up hits, but not in bunches. He didn’t give many free passes, wasn’t saved by double plays (18 on the year), and didn’t appear to fatigue or change as the season went on, deep into the playoffs.

In those playoffs, not much changed. He pitched in two of the four games of the NLCS, then in every single one of the five World Series games. He pitched full, clean innings in each appearance, going 1 or 2 in most, with 3 in the final game, closing things out for the win.

It’s safe to say that what Marshall did was unusual, but it doesn’t look like anything special aside from the sheer number of outings. Marshall didn’t tire, making his season look extremely consistent among the seemingly random outings.

I think one of the keys, seldom noted, is that Marshall’s 1974 season was extreme, but it was in pattern for him. He led the league in appearances every year from 1973 to 1975, going up from 65 to 92, then up to 106. He was down to 58 in 1975 with discernibly lower strikeout numbers. His K/BB ratio declined for the rest of his career, though he did have 90 appearances for the Twins in 1979. At age-36, it’s hard to say that this was anything aside from a one-year blip amidst a normal decline in his thirties. I don’t think it’s fair to say that the decline was brought on by the 1974 workload, though it can’t be ruled out either.

Here’s where we get into a bit of speculation. I reached out to Dr. Marshall by email, but did not receive a reply, so I wasn’t able to confirm any of this. Marshall was doing a lot of research on himself for his PhD in kinesiology at Michigan State back in the late 1960s. There’s a lot of film - some that has been shown in his presentations - that show him pitching. My guess is that Marshall was throwing a lot more than normal during his off-season, which increased his chronic workload. By the time he got to camp, he was well conditioned to throw more than others and by that availability, started to build a reputation as a guy who could throw a lot, albeit not one that showed great results for admittedly bad teams in his first few seasons.

I did manage to talk with Charlie Hough, who remembered Marshall’s preparation. “Well I think we get more tired mentally than physically. Mike’s conditioning stuff was lifting weights, he used to throw a shotput,” he explained. “Yeah, he did some rather exotic workouts which I couldn’t do. But he did some workouts that maintained his strength, and he was adamant that it worked, and doggone-it, it did. Now it’s started again. Guys are starting to do those kinds of workouts: long tossing and stuff. I can’t imagine that he got tired.”

“He was something totally different then the rest of us,” Hough continued. “And he, like I said, there’s pitchers today doing these conditioning things with heavy ball, light ball, and all this conditioning - he was doing that in the 70’s. He was way ahead of the curve on that. He was one of a kind and was kind of a, I guess you’d say, an odd duck back then, and today he’d be very much accepted.”

If Marshall’s off-season workouts made him a proto-Bauer, not taking time off in the off-season, and holding a very high chronic workload, then the day to day pitching would have been easier to manage than something like Nolan Ryan going every fourth day. Marshall likely threw more on the side and on his so-called off-days, as he currently advocates and in some stories that have been shared by people like Tommy John and Jim Bouton. That would maintain that chronic workload, allowing for a safe and steady workload, if only someone would allow it.

The chronic workload necessary for something like this is insane - about 65 - and unprecedented in the known data for baseball. That’s not to say it’s impossible. I am curious what the peak chronic workloads for someone like a Trevor Bauer have been over the past few off-seasons, though I know he doesn’t do anything like throw 100 pitches a day.

In fact, we may be looking at the wrong sport. In professional cycling, the workload units put up in race and training by Tour de France level riders is similarly insane, putting up hundreds of miles at speeds in excess of 30mph in the peloton, day after day, mountain after mountain. While an endurance sport like cycling is different in terms of its energy systems that a high effort burst activity like pitching, studies continue to show that the basics behind workload systems hold across sports.

Recent work done by the Sub 2 Project, which is attempting to help a human run a marathon in under two hours, has brought out some interesting physiological data that could have some application to pitching. Their focus on training, preparation, biomechanics, and more don’t have direct application to pitching, but they certainly can be applied. Could Marshall have simply created a system for himself that echoed this, putting him well out in front of others but not recreated simply because it was difficult and few listened to him?

By the time he got to Montreal in 1970, he was likely physically ready to be an everyday pitcher, but his effectiveness didn’t allow that. Something clicked in 1971 and my guess is that it was command of his screwball, which would become his best pitch, and working with a pitching coach that was as iconoclastic as himself, in Cal McLish. (McLish has one of the great names of all time: Calvin Coolidge Julius Caesar Tuskahoma McLish is on his birth certificate and tells you a lot about the man.)

It’s that quirky pitch — both the rarity of a screwball and the bigger rarity of a right-handed screwball — that many have cited for Marshall’s success. There’s no way to tell how much he used it or how, but in modern baseball, there is something of an equivalent — the circle change. Both pitches are thrown with heavy pronation, a “empty the can” movement. It’s hard to explain so watch this video:

The movement of the pitches is roughly the same. From a right handed pitcher, the ball is essentially a reverse slider, moving down and in to a right handed batter. Here’s where things get a little interesting - Marshall had no platoon split at all, with a 666 OPS against righties and a 670 OPS against lefties. I honestly can’t think of a pitcher who’s that equal against both and the ability to use both a screwball and a curve against batters from either side is equally unusual.

(I should note that Marshall used a fastball, curve, and screwball. He had a change, but seemed to seldom use it, though again, there’s no public records of this. If the screwball was acting as a functional change, it makes sense. I’m going by mentions in stories over the years, which is anecdotal at best. The curve he threw seems to be different over the years, which leads me to think it went from slider to curve or curve to slider on a continuum over the years.)

While baseball didn’t often use matchup relievers at that point, looking at Marshall’s teammates offers a clue. Geoff Zahn had a similar lack of platoon split over his career, but in 1974, he did - 637 to righties, only 522 to lefties. Jim Brewer was a lefty who was Zahn’s opposite - 554 to righties, 763 to lefties. Both of these pitchers were used most often against lineups that leaned to their advantage, which indicates Alston understood platoon advantages.

Alston also wasn’t scared of a “gimmick” pitch like Marshall’s screwball. Charlie Hough was the next best reliever on the team and exclusively threw his knuckler. Hough had a more normal platoon split, almost 100 points better against righties, but more notably gave up more walks without more strikeouts. Alston wasn’t afraid to use Hough in any situation, but it was clear that Marshall was better. Alston merely used his better pitcher more often.

The platoon splits for the Dodgers starters were also relatively normal - both Andy Messerschmidt and Don Sutton had around a 100 point difference. That means that when facing an alternating lineup, Marshall’s advantage grew, which not only made him effective, but made him useful in more innings. Stack lefties on him? No advantage. Left-right march him? No advantage. There wasn’t an inning that looked different to him on a lineup basis, so why not give him more?

There’s another key here in that Marshall threw a lot of innings, but seldom more than 3. In his 106 outings, he only saw batters a second time in 14 of them and in only one did he see batters a third time. The advantages of this are well-known for starters and hold true for someone like Marshall. One interesting thing is that even when he faced a team multiple times in a series or even over a season, he didn’t appear to lose the advantage. This is tough to discern from available data, so I don’t want to put too much emphasis on it.

It’s unclear if Walter Alston knew all these things. If I’d thought of it a couple months or years ago, Tommy Lasorda likely would have known and told the story. This is what we lose when someone like him dies, but then again, Marshall is alive.

A couple things combine - Marshall’s ability to handle workload, his consistency, his lack of platoon splits, and that teams seldom saw him twice around. Marshall had good, confident, and slightly iconoclastic coaching, worked with short bullpens, and was clearly on a good team with solid defense.

Everything was working for him, but that can hardly be unique to baseball. He had teammates and other relievers of the era made a lot of appearances. In 1974, there were three other pitchers who had 70 or more appearances, though none more than Larry Hardy’s 76. (By the way, Hardy was listed at 5’10, 180, exactly the same as Marshall. That said, Hardy only threw two innings the following year and was out of baseball after 1976.)

My theory is that Marshall’s talents combined to allow him to show that an extremely high chronic workload, maintained over the course of multiple years, is in fact possible. All it’s going to take to test it is a team willing to try it. 14 pitchers had 70 or more appearances in 2019, led by Alex Claudio’s 83. The difference is that Claudio only pitched 63 innings over those outings. While Claudio did have a platoon split, he was used relatively equally against both sides. Add in that the '19 Brewers used thirty total pitchers in 2019, compared to the 12 that the ‘74 Dodgers did and you can see why heavy usage wasn’t an issue that concerned Craig Counsell.

What Marshall did shows that this is possible. What we don’t know is the how and it’s nearly impossible to test. With modern training techniques, it should be easier to recreate what Marshall did, but there’s simply no substitute for the hard, continual work that builds up an arm. Marshall has clearly been outside the norms while a player, but his irascible nature and inability to compromise on his systems may have kept the rest of us behind where he was. I don’t believe Marshall was singular in his ability to sustain this kind of workload, I just think he got there first.