For the last few months, David Barshop has been doing a lot of work behind the scenes on the newsletter. He had some ideas for articles and his idea for a series on baseball’s changes in 2020 and how they were perceived struck me as a great idea. I hope you’ll enjoy this, the first in a series, as much as I did.

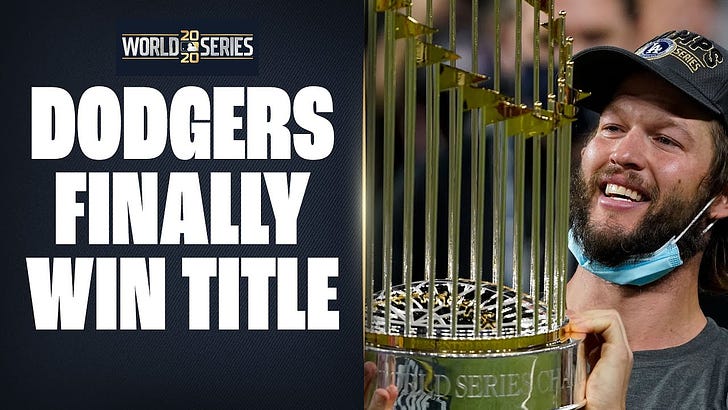

What was Major League Baseball in 2020? This is the question I have tirelessly tried to answer since late October when my beloved Dodgers captured their seventh World Series – and first in my lifetime. While I have yet to adequately answer this question, I feel confident in declaring that what we saw in 2020, whatever it was, was not your grandfather’s MLB.

I was fascinated at how the 2020 season played out. At the conclusion of the World Series, as my Dodgers won, strangely, I felt nothing. I couldn’t help but wonder if other Angelenos faithful to the Dodger blue felt the same?

Watching the players hoist the trophy somehow didn’t feel special, as if my heart had put an asterisk on this shortened, strange pandemic-altered season. It’s as if baseball’s most coveted Sterling Silver prize was now tarnished in my eyes, rather than appearing glistening and polished.

These sentiments caused me to examine the strangeness that was, the 60-game MLB season. In doing so, I hope to understand why MLB 2020 feels like an aberration at best, and an asterisk at worst.

Some say money is a core cause of strife within professional sports. The MLB offseason is proof of harrowing reality. Following weeks of contentious negotiations, the MLBPA and the owners compromised on a 60-game schedule with the players receiving 37% of their annual salaries. This compromise, like any good compromise, left both parties relatively unhappy. Baseball nets approximately 40% of its revenue from fans walking through the turnstiles and in 2020 baseball’s 30 teams combined for 3 billion dollars in lost revenue opportunities as result of the 898 regular season games being played without any fans in attendance. MLB franchises this offseason ended up firing or furloughing hundreds of team employees in an effort to cut costs.

Although concern over severe revenue shortfalls threatened the season’s mere existence, it was the unexpected rule changes that threatened baseball’s integrity more than an amount of money (or lack thereof) ever could.

Baseball was different in 2020. But, to fully grasp the historical significance of the aforementioned “difference,” and the true extent of what I now call a “tarnished trophy” as I now see to see it, we must first delve into the plethora of inauthentic and unsavory rule changes we saw in 2020.

If you don’t have four hours, you probably can’t watch an entire MLB game from the first pitch to the final out. Pace of play is an issue for the league. In the past, we’ve seen small changes implemented to shorten game time. The 20 second pitch clock (which goes mostly unheeded), the automatic intentional walk, limitation on mound visits, and a reduction of time in between innings have indeed contributed to faster games. To the baseball purists who find these alterations unjust, I respectfully disagree. These adjustments dramatically change the integrity of the game.

Having said that, the COVID-influenced changes to the rulebook were, well…more intrusive, cheapening the way the game was played.

For instance, the decision to place a runner on second base to start every extra inning: The goal was primarily to shorten game time, and get players off the field as quickly as possible. But the result was changing the way the game was called as a pitcher, as a catcher, and most importantly as a manager.

The new designated runner rule was not as universally displeasing. Some even welcomed change as a chance to see increased scoring opportunities and strategies. Conversely, others (including myself) see nothing but a big ol’ “asterisk” next to every game that went past nine innings.

With respect to the rules, aside from the designated hitter, baseball has stayed mostly steadfast and traditional since 1882. For this reason, fans likely wince which is probably when a vital tenant of America’s pastime evolves to something new.

Heartbreak and sport often go hand-in- hand. I’ve waited over three decades to see the Dodgers win the whole thing, but as they celebrated on the field following the final out, I wondered, “if this World Series was ‘legitimate’ or is it “fraudulent,” not unlike the 2018 Astros World Series victory, which was marred by sign stealing. Or, was it sinful and sacrilegious in the same manner that the 1919 White (Black) Sox World Series was?

With so many rule changes that compromised the integrity of the game, it’s worth contemplating the comparability this season now possesses. Can it be juxtaposed by any other year, or must it now stand alone for all of bat-and-ball eternity? The fact that Edwin Rios of the Dodgers hit the first 2-run leadoff home run-in major-league history this year only leaves me more conflicted as to any of the “history” made on the diamond in 2020.

Baseball’s moniker, America’s Pastime, places unique pressures on this game to maintain its long-standing traditions while, simultaneously placing every game and every statistic into a larger historical context.

How can that trend continue after what we have seen this season?

Any aberration in the integrity of the game not only riles fans up, but also leads to questions as to how we incorporate these changes and still adequately compare from year to year and era to era.

Sadly, the use of an asterisk has become commonplace in sport and beyond. Denoting an accomplishment with an asterisk has become a means of finding solace in change. Major League Baseball is no exception. For instance, the so-called “Steroid Era” in baseball has led to several asterisks being attached to the sport. And, while the baseball purists will hate me for saying this, this occurred because steroids were, at the time, unfortunately commonplace.

Steroids too, and the asterisks that routinely accompany them only blur the lines even further. Quite frankly, they create more questions and convolute matters more.

Are Barry Bonds’ 73 home runs in 2001 the single season record? Is Roger Maris’ 61 home runs in 1961, the first year of Major League Baseball expanding the regular season to 162 games the record?

According to one expert, baseball historian and DePauw professor Dave Bohmer, the asterisk likely renders the achievement incomparable.

Bohmer came to this conclusion through his work writing a book on former baseball commissioner Ford Frick, who acted in that capacity from 1951 to 1965, an ever-changing time in the history of Major League Baseball.

“Frick declared achievements are no longer comparable if 61 homers were achieved after 154 games, the record would have to be treated with ‘a separate mark,’” Bohmer said of Frick.

Similarly, a New York reporter later stated that it sounded like an asterisk would be placed by the record and the association stuck, even though the specific reference to an (asterisk) was never mentioned.

It wasn’t until 1991, more than 20 years after his career ended (and six years after his death) when Fay Vincent and an 8-person panel aptly designated, “the committee for statistical accuracy,” ruled to drop the asterisk from Roger Maris’ record.

Doing such, even decades later, affects the historical perspective in which we view the achievements and accolades of those who have played this majestic game.

But, does it change the average fans view of said home run title? According to what Bohmer said of Frick, it does. It likely does to your average fan as well.

Now that we’ve gotten some of these vexing perplexities out of the way – as best we can anyway – let’s look at how the extra inning rule actually changed the game (statistically speaking) in 2020.

Because we only had 60 games per team, simply multiplying 60 by 2.7 to get 162, won’t accurately do justice to any comparisons we’d want to make with 2019. Simply put, there are far too many unknowns to make any predictions as to how many of these 102 un-played games per team would make it to extra innings.

Rather, let’s look at percentages. According to the Elias Sports Bureau, there were 68 regular season games that went into extra innings, and the two longest running games of the year both ended in the 13th inning.

In 2019, the percentage of extra inning games which ended in the tenth inning was 43.8%. Comparatively, in 2020, 68.2% of extra-inning games were settled by the tenth inning.

With respect to the eleventh inning, 2019 saw 71.6% games end in this frame. In 2020 however, that percentage of games ended after the inning number eleven rose dramatically to 90.9%.

As for twelve-inning games, 2020 saw 95.4% of the games finish by inning number twelve, up nearly 13% from 2019 when just 82.2% ended after the twelfth stanza.

And while no games this year went to inning fourteen in the shortened sprint of an MLB season, approximately 11.1% of all extra-inning games went into the inning fourteen or beyond in 2019.

So, what do these figures mean?

Simply that attempting to put a cap on a game that has no time limit is antithetical to baseball. The game’s lack of a clock is a large part of what makes it one-of-a-kind.

In fact, if these figures show anything, it is that these numbers show how the extra inning runner rule did indeed achieve its goal of shortening extra-inning games, but it certainly influenced the end result of those games. Said another way, it influenced who won and ultimately who lost these games.

Again, I’m left to ponder, how do fans (including myself) resist the urge to look at every one of those games as an asterisk, especially in a 2020 season that will be eternally linked with that ugly black mark of annotation.

Furthermore, extra-inning adaptation unique only to 2020, was abandoned for the postseason.

If anything can be gleaned from this inauspicious attempt, it is that if this rule was as good for the game as Manfred had indicated, he wouldn’t have eradicated it on the sport’s biggest spectacle.

Logically, one would assume that this means an end to the extra-inning runner-at-second rule permanently.

However, after the regular season ended, in an interview with Jon Heyman and Tony Gwynn Jr. on the “Big Time Baseball” podcast Rob Manfred equivocated otherwise: "If I had to handicap them, I think I would say that the extra-inning rule probably has the best chance of surviving,” Manfred said. “I think that most people came to realize that the rule adds a layer of strategy and sort of a focus at the end of the game that could be helpful to us over the long haul, so I give that one the best chance.”

These comments are very surprising and nothing short of a head-scratcher for me. I say this because the universal DH rule (yet another byproduct of a wild and wacky 2020) did just the opposite – it reduced virtually all the strategy that comes with utilizing a DH in the precisely perfect moment.

That precisely perfect moment is the beauty of baseball personified. Coaching baseball is about managing (and succeeding in) intricate moments of a game by way of a myriad of managerial decisions: double switches, pitchers bunting and hitting and more. These elements were all essentially removed from the game as a result of the designated hitter.

Equally perplexing, Manfred’s feels that the rule was embraced by most players. In reality, the opposite was true. “It’s not real baseball, but it’s fine for this year” said Clayton Kershaw. “I hope we never do it again…”

Former Indians’ ace turned San Diego Padre Mike Clevenger was far less diplomatic in expressing his distaste for the extra inning protocol, calling it, “the whackest s—t I’ve ever seen.”

Inevitably, how the player satisfaction will play a large part in whether these rules pertaining to designated runners and hitters alike are adopted indefinitely or dropped permanently. The power of the players union can be quite the powerful tool.

Personally, I hope this is the last we ever see of either rule.

Many changes in life and in sports were needed to survive 2020. While 2021 will take a vastly different shape then its predecessor, both on the diamond and off, (or so we hope) we need to learn from our mistakes. For Rob Manfred and the MLB learning from your mistakes means two things and one friendly piece of advice:

Abandon both these nonsensical (albeit well-intentioned) designated runner and designated hitter rules. While each rule did its part in shortening extra-inning games in the name of player safety, it took away a lot of what makes baseball unlike any other sport. Regrettably, the commissioner’s office fell flat in maintaining the integrity and class of the game with these experiments’ shoddy experimentation. The disappointment was palpable amongst those with a true love for the longevity and consistency of this game.

Abandon the asterisks. Baseball is fraught with statistics and other numerical representations indicative of superior athletic ability when using a bat, ball, glove and a baseball diamond. That said statically-charged displays of athletic greatness cannot be compared or evaluated unless they were achieved under similar circumstances and constraints. Any instance where an asterisk was present connotes that it was not indeed a level playing field.

If you wish to keep the asterisk, then you must separate the statistical achievement and the historical record. Those with an asterisk go in one book. Those without an asterisk in another.

This is not a perfect solution, but it is a step in the right direction…because what I saw of the MLB was not my Grandfather’s baseball and it damn sure isn’t what I want Major League Baseball to be moving forward.